Medication Benefit-Risk Calculator

Your Situation

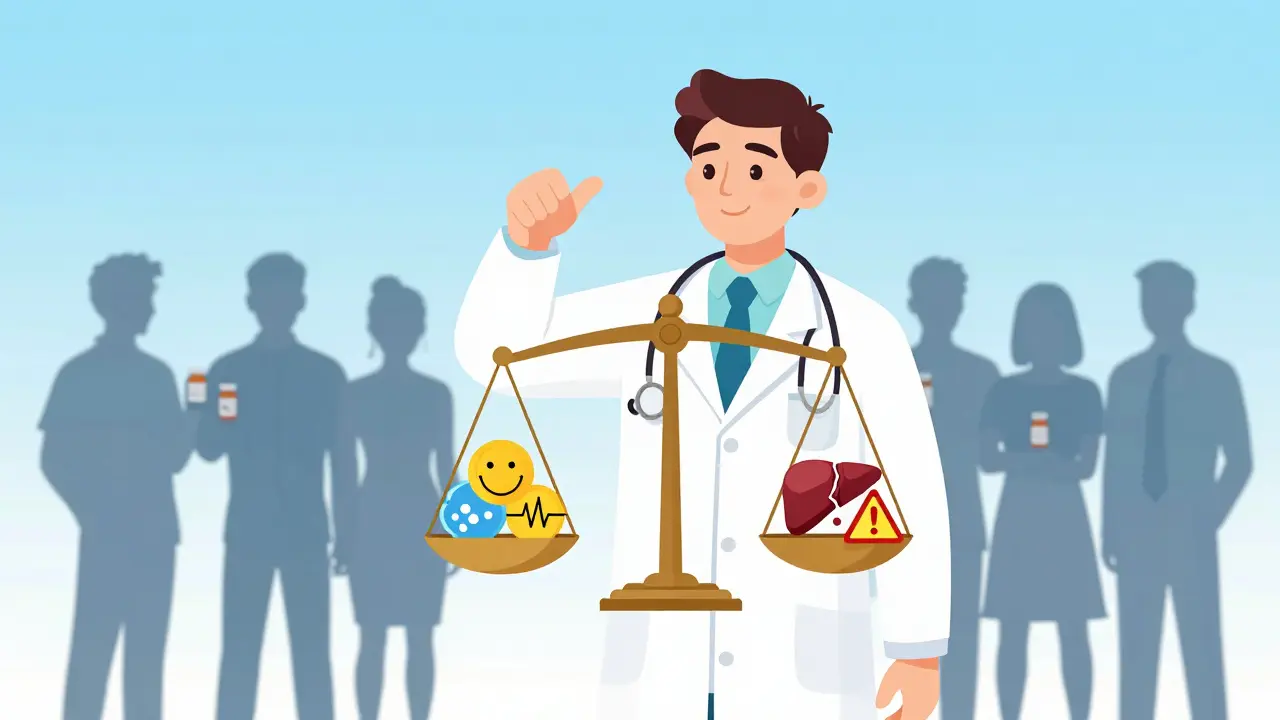

Every time a doctor prescribes a pill, they’re not just handing out a cure-they’re making a bet. On one side: relief from pain, better blood pressure, slower cancer growth. On the other: nausea, liver damage, rare but deadly reactions. This isn’t guesswork. It’s a deliberate, evidence-based calculation called benefit-risk assessment. And it’s the single most important step in deciding whether a medication should be used at all.

It’s Not About Eliminating Risk-It’s About Managing It

No medication is risk-free. Even aspirin can cause internal bleeding. Antibiotics can trigger life-threatening allergies. Chemotherapy kills cancer cells-but also destroys healthy ones. The goal isn’t to find a drug with zero side effects. That doesn’t exist. The goal is to find the drug where the good outweighs the bad-for this patient, with this condition, at this stage of life. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) made this official in 2013. Their framework says: a drug gets approved only if its benefits are expected to be greater than its risks. That’s the baseline. But in practice, it’s way more personal than that. A drug that’s too risky for a healthy 45-year-old might be the only hope for someone with terminal cancer. One patient’s dangerous side effect is another patient’s lifeline.How Doctors Actually Do the Math

It’s not a spreadsheet. But it’s structured. Doctors start by asking four questions:- How bad is the disease? A migraine is awful-but not life-threatening. Pancreatic cancer is. The worse the condition, the more risk doctors will accept.

- What else is available? If there are five other drugs that work just as well with fewer side effects, why pick the riskier one? But if there’s only one option-like Zolgensma for spinal muscular atrophy-then even a $2.1 million price tag and serious liver risks become acceptable.

- How strong is the benefit? Does the drug reduce stroke risk by 25%? Extend life by 18 months? Improve mobility by 30%? These numbers matter. A 70% tumor shrinkage rate in a clinical trial is powerful. But if that only happens in 1 out of 10 people, the picture changes.

- How bad are the side effects? Is it a headache? Or a 1 in 100 chance of sudden heart failure? Are side effects temporary? Or permanent? Can they be monitored or reversed?

Patient vs Doctor: Who Decides What’s Worth It?

Here’s where things get messy. Doctors and patients often see risk differently. A 2023 survey by the Michael J. Fox Foundation found that 65% of Parkinson’s patients would accept a 20% risk of uncontrolled movements (dyskinesia) if it meant a 30% improvement in walking and balance. Doctors, on average, thought patients would only tolerate a 12% risk. Why? Because doctors think in terms of statistics. Patients think in terms of their daily lives. A 2022 study in the journal PMC found patients with chronic conditions care more about feeling better today than living longer tomorrow. They’ll trade a longer life for a better quality of life-by a 3-to-1 margin. That’s why the FDA now actively collects patient input. Since 2016, they’ve held over 100 public meetings with patients across 20 diseases. A woman with multiple sclerosis might say: “I’d take a drug that makes me tired every day if it stops me from needing a wheelchair.” That’s not a number in a trial. That’s a life decision.Why Some Drugs Get Rejected-Even When They Work

Not every effective drug gets approved. The FDA turned down several new heart drugs in 2022-not because they didn’t lower cholesterol or blood pressure, but because they increased bleeding risk too much. Why? Because the patients were low-risk. They didn’t have heart disease yet. They were healthy people trying to prevent it. For them, a 0.1% chance of internal bleeding wasn’t worth a 5% drop in stroke risk. The benefit didn’t outweigh the risk. In contrast, for someone with advanced heart failure, that same drug might be a no-brainer. Same drug. Different patient. Different outcome. This is why personalized medicine is the future. Right now, most benefit-risk decisions are based on averages from clinical trials. But those trials mostly include white, middle-aged men. A 2023 JAMA Network Open study found that 75% of trial participants were White-even though minorities make up 40% of the U.S. population. That means we might be missing how side effects hit different groups. A drug that’s safe for one ethnicity might cause liver damage in another. We’re starting to fix this-but slowly.What Happens After the Prescription Is Written

The job doesn’t end when the patient walks out the door. Monitoring continues. That’s called pharmacovigilance. Pharmaceutical companies are required to track side effects after a drug hits the market. The global market for this work is worth $7.8 billion-and growing fast. Why? Because real-world data often shows problems clinical trials miss. A side effect that happens in 1 in 1,000 people won’t show up in a trial of 500 patients. But once millions are taking the drug? It shows up. That’s how we learned about the rare blood clots linked to some COVID vaccines. Or how we found out that certain diabetes drugs increase the risk of heart failure in older adults. These discoveries change prescribing habits. Doctors now spend 15 to 20 minutes per visit just talking about risks and benefits. That’s the most time-consuming part of prescribing, according to the American Medical Association. And it’s not just about listing side effects. It’s about helping patients understand what “10% risk” really means. Studies show only 35% of patients know that means “1 in 10 chance.” So the FDA created 47 free decision aids-simple tools that show risks visually, with icons and charts. At Mayo Clinic, these tools cut medication non-adherence by 22%.

The Future: Personalized Risk, Not One-Size-Fits-All

By 2030, benefit-risk assessments won’t be based on population averages. They’ll be built for you. Your genes. Your liver function. Your diet. Your sleep patterns. Your other medications. All of it will feed into a model that predicts: What’s the chance this drug will help you? What’s the chance it will hurt you? AI tools are already doing this. Roche’s ARIA platform uses machine learning to spot safety signals in electronic health records. It found real-world side effects 30% faster than traditional methods. The goal? To stop giving the same drug to everyone. To say: “For you, this drug has a 72% chance of working and a 5% chance of causing liver damage. For your neighbor, it’s 40% and 18%.” That’s precision prescribing. It’s not here yet. But it’s coming. And when it does, the old idea of “one size fits all” will be gone.Bottom Line: It’s a Conversation, Not a Command

Medication decisions aren’t made by algorithms. They’re made in rooms-with doctors, patients, and families talking through trade-offs. A drug might be statistically “safe.” But if the patient is terrified of needles, or hates taking pills, or can’t afford the co-pay, the benefit disappears. That’s why the best doctors don’t just recite risks. They ask: What matters most to you? What are you willing to give up? What are you afraid of? The answer isn’t in a clinical trial. It’s in the person sitting across from them.Why do some medications get approved even if they have serious side effects?

They’re approved when the condition being treated is severe and has few or no alternatives. For example, cancer drugs often cause nausea, hair loss, or immune reactions-but if they double survival time, most patients accept those trade-offs. The FDA only approves drugs where the benefits clearly outweigh the risks for the intended population.

Do patients understand the risks of their medications?

Not always. Studies show only about 35% of patients correctly interpret phrases like “10% risk of side effects” as “1 in 10 chance.” Many overestimate rare risks (like allergic reactions) and underestimate common ones (like dizziness or fatigue). That’s why doctors now use visual tools-charts, icons, and analogies-to make risks clearer.

Why do doctors sometimes prescribe drugs that aren’t the safest option?

Because safety isn’t the only factor. Effectiveness, cost, ease of use, and patient preference matter too. A drug with mild side effects might not work well enough. A safer drug might require daily injections. Another might cost $10,000 a month. The best choice balances all these factors-not just one.

How do regulators decide if a drug’s risks are too high?

Regulators like the FDA use a structured framework that looks at four things: the severity of the disease, what treatments already exist, how strong the drug’s benefits are, and how serious and common the side effects are. They also consider whether risks can be managed-like through monitoring, special training for doctors, or restricted distribution. If the benefits are strong and the disease is life-threatening, they’ll accept higher risks.

Are some groups of people at higher risk from medications?

Yes. Clinical trials have historically included mostly white, middle-aged men. That means side effects in women, older adults, or racial minorities might not be fully understood until after the drug is on the market. For example, some blood pressure drugs work less well in Black patients, while others cause more swelling. Newer research is pushing for more diverse trials to fix these gaps.

Benefit-risk assessment isn’t perfect. It’s messy, emotional, and sometimes inconsistent. But it’s the best system we have to keep people safe while giving them real hope. And as medicine gets more personal, it’s becoming more human, too.

Gerard Jordan

January 21, 2026 AT 06:59michelle Brownsea

January 21, 2026 AT 13:33Roisin Kelly

January 23, 2026 AT 07:47Samuel Mendoza

January 24, 2026 AT 10:44Yuri Hyuga

January 26, 2026 AT 08:29Coral Bosley

January 28, 2026 AT 06:42Steve Hesketh

January 28, 2026 AT 17:48shubham rathee

January 29, 2026 AT 15:47Kevin Narvaes

January 30, 2026 AT 22:47Alex Carletti Gouvea

February 1, 2026 AT 02:42Ben McKibbin

February 2, 2026 AT 23:37Rod Wheatley

February 3, 2026 AT 23:03Ashok Sakra

February 4, 2026 AT 03:12lokesh prasanth

February 4, 2026 AT 10:54Glenda Marínez Granados

February 5, 2026 AT 19:05