When you take a pill for high blood pressure, diabetes, or cancer, you expect it to help. But sometimes, it causes unexpected problems-rash, diarrhea, muscle pain, or even heart issues. Why does this happen? It’s not always a mistake. In fact, side effects often come from two very different places: on-target and off-target effects. Understanding the difference isn’t just for scientists-it affects every patient who’s ever had to stop a medication because it didn’t sit right.

What Are On-Target Effects?

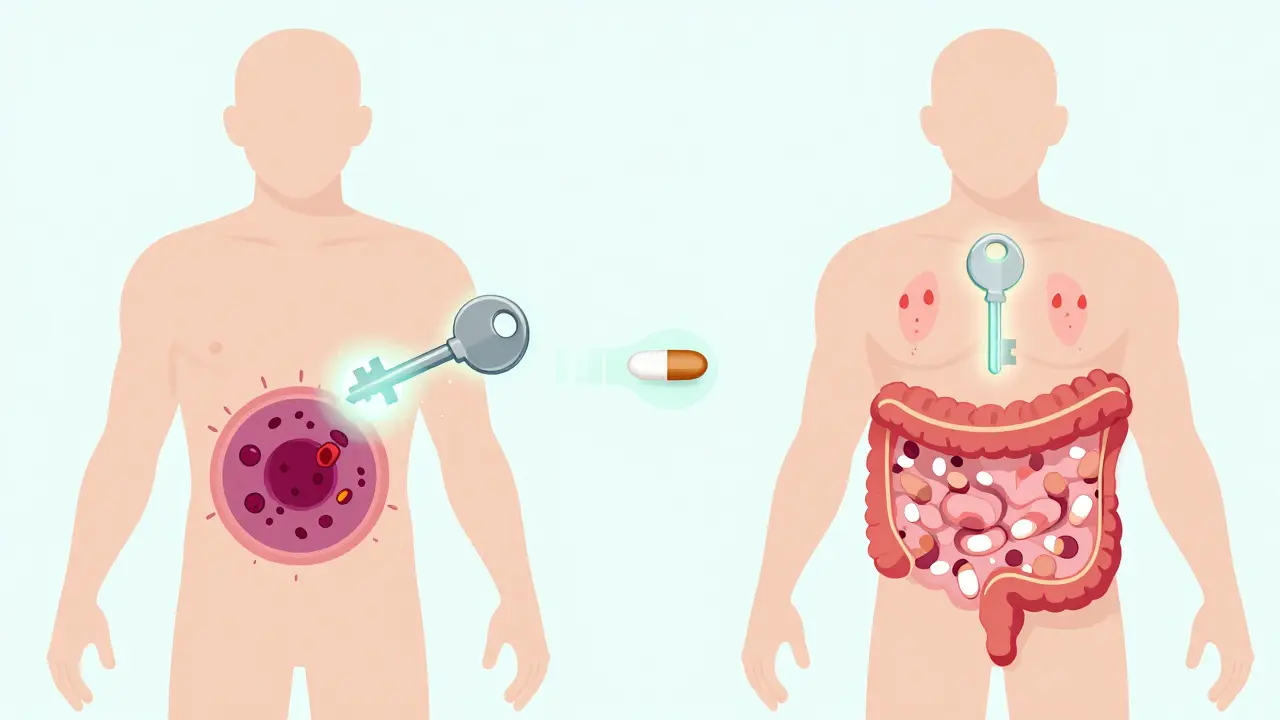

On-target effects happen when a drug does exactly what it’s supposed to do-but in the wrong place. Think of it like a key that fits perfectly in a lock. The lock is your intended target, say, a protein that drives tumor growth. The drug unlocks it, shuts it down, and stops the cancer. Simple. But that same protein might also be active in your skin, gut, or heart. When the drug hits it there too, you get side effects that are actually the drug working as designed-just too broadly. Take EGFR inhibitors for lung cancer. These drugs block a protein that helps cancer cells grow. But EGFR is also vital for skin repair. So, 68% of patients on these drugs get severe rashes. It’s not a bug. It’s a feature. Same with metformin for type 2 diabetes. It lowers blood sugar by making the gut absorb less glucose. That’s the goal. But it also causes diarrhea in up to 30% of users-because the drug is doing its job too well in the intestines. These aren’t random reactions. They’re predictable, dose-dependent, and often manageable. Doctors expect them. Patients just need to know they’re normal.What Are Off-Target Effects?

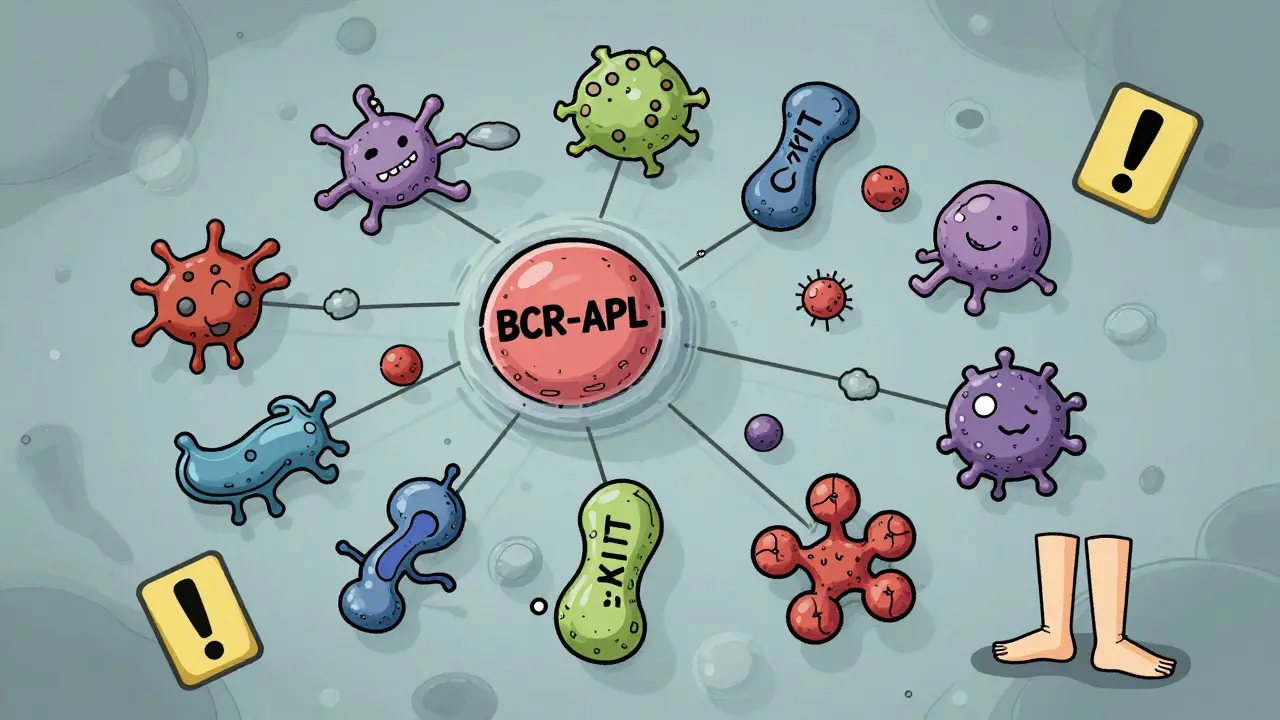

Off-target effects are the surprise guests at the party. The drug wasn’t meant to interact with them, but it does anyway. These happen because drugs aren’t perfect keys. Even the best ones can nudge open a few other locks-sometimes similar ones, sometimes completely unrelated. Kinase inhibitors, used in cancer and autoimmune diseases, are notorious for this. One drug might bind to its main target, BCR-ABL, to treat leukemia. But it also sticks to c-KIT, a different kinase involved in immune function. That’s why patients get swelling in their legs or fluid buildup-side effects that have nothing to do with killing cancer cells. Studies show that small molecule drugs average over six off-target interactions at normal doses. Some kinase inhibitors bind to 25 or more proteins. That’s not a flaw in the patient-it’s a flaw in the molecule’s design. Even common drugs like statins, used to lower cholesterol, can cause muscle damage in rare cases. That’s off-target. The drug’s main job is to block HMG-CoA reductase in the liver. But in some people, it accidentally interferes with muscle cell energy production. That’s why doctors check CPK levels. If they spike, it’s not the disease-it’s the drug hitting the wrong target.Why Do Some Drugs Have More Off-Target Effects Than Others?

Not all drugs are created equal. Small molecules-pills and capsules-are more likely to wander. They’re small, flexible, and can slip into places they weren’t meant to go. Biologics, like monoclonal antibodies (think Herceptin or Humira), are much bigger and more precise. They’re designed to lock onto one specific protein like a magnet. That’s why they usually have fewer off-target effects. But they’re not immune. Herceptin can still cause heart problems-not because it hits the wrong protein, but because HER2, its target, is also important in heart muscle cells. That’s an on-target effect in disguise. A 2018 analysis in Nature Reviews Drug Discovery found that small molecules average 6.3 off-target interactions. Biologics? Just 1.2. That’s why companies are shifting toward biologics when possible. But they’re expensive to make. So, the trade-off isn’t just medical-it’s economic.

Can Off-Target Effects Ever Be Good?

Yes. Sometimes, what looks like a side effect turns out to be a breakthrough. Sildenafil (Viagra) was originally developed to treat angina. It worked-on blood vessels in the heart. But patients kept reporting something else: improved erections. Turns out, the drug also relaxed blood vessels in the penis. That was an off-target effect. Now, it’s the main use. Thalidomide is another example. Originally pulled from the market in the 1960s because it caused severe birth defects, it was later found to calm the immune system. Today, it’s a key treatment for multiple myeloma. The same molecule, same off-target effect-different disease, different outcome. This isn’t luck. It’s why some drug companies now use phenotypic screening-testing compounds on whole cells or animals instead of just one protein. You might not know the exact target, but if the drug improves the disease, you follow it. About 60% of first-in-class drugs approved between 1999 and 2013 came from this approach.How Do Scientists Tell Them Apart?

It’s not easy. You can’t just look at symptoms. A rash from an EGFR inhibitor looks the same as a rash from an allergic reaction. So researchers use smarter tools. One method is gene expression analysis. Scientists treat cells with the drug, then see which genes turn on or off. If those changes match what happens when you delete the target gene using CRISPR, it’s likely on-target. If the changes are different-especially in immune or stress pathways-it’s probably off-target. Another tool is chemical proteomics. They attach the drug to a bead and pull out every protein it sticks to in a cell. It’s like casting a net and seeing what else you catch. This is how they found that statins bind to over 100 proteins-not just HMG-CoA reductase. The FDA now requires companies to test for off-target effects using at least two different methods. That’s new. Ten years ago, many skipped this step. Now, skipping it can kill a drug’s approval.

Kim Hines

December 16, 2025 AT 20:14Had no idea my chronic diarrhea from metformin was just the drug doing its job too well in my gut. Kinda makes me feel less like a broken person and more like a walking pharmacology experiment.

Joanna Ebizie

December 18, 2025 AT 00:35So let me get this straight - the drugs that make you miserable are technically working? That’s not a bug, it’s a feature? Sounds like Big Pharma’s way of saying ‘you’re just not special enough to be side effect free.’

Ron Williams

December 18, 2025 AT 21:32It’s wild how much we assume medicine is precise. We think pills are like laser scalpels, but really they’re more like throwing a handful of glitter into a fan and hoping the right pieces hit the target. The fact that any of this works at all is kinda miraculous.

Kitty Price

December 19, 2025 AT 10:10Viagra being a happy accident still blows my mind. Imagine being like ‘uhh… doc, this angina med is giving me… other results?’ and then boom - billion dollar industry. 🤯

Aditya Kumar

December 19, 2025 AT 18:59Too much info. I just want my pill to work without me having to study biochemistry.

Colleen Bigelow

December 21, 2025 AT 13:25They’re hiding the truth. Why do you think they don’t tell you about the off-target effects? It’s because they don’t want you to know how many random proteins these drugs are hijacking. This is chemical warfare on your body and they’re calling it ‘medicine.’

Billy Poling

December 23, 2025 AT 09:32While I appreciate the attempt at simplifying complex pharmacological mechanisms, I must respectfully assert that the conflation of molecular binding affinity with clinical phenotypic outcomes introduces a significant epistemological gap that may mislead non-specialist readers. The notion that ‘on-target’ side effects are inherently predictable is an oversimplification, as tissue-specific expression patterns and epigenetic modulation can introduce profound variability even within genetically homogenous populations. Furthermore, the assertion that biologics exhibit fewer off-target effects neglects immunogenicity cascades and Fc receptor-mediated downstream effects, which are not captured in standard proteomic screens. The FDA’s current guidance, while an improvement, still lacks standardized thresholds for acceptable polypharmacology, leaving clinicians to navigate a landscape of probabilistic risk rather than deterministic safety.

Randolph Rickman

December 24, 2025 AT 11:42Love this breakdown. Seriously. So many people panic when they get a side effect, but knowing it’s either ‘the drug working too well’ or ‘the drug being a clumsy guest’ makes it so much easier to talk to your doctor. You’re not broken - your meds are just messy. And that’s okay. We’re learning how to clean them up.

sue spark

December 25, 2025 AT 20:20so like if my rash from the cancer drug is on target then its not an allergy right like i shouldnt stop it unless its bad

SHAMSHEER SHAIKH

December 26, 2025 AT 06:05As a physician practicing in rural India, I have witnessed patients discontinuing life-saving medications due to misunderstanding of side effects. The distinction between on-target and off-target effects is not merely academic - it is a matter of survival. Many patients believe that diarrhea or rash means the drug is ‘poisoning’ them. Education, delivered with patience and clarity, can transform compliance. I have started using analogies - ‘the drug is a skilled carpenter who accidentally hit his thumb’ - and it works. We must prioritize patient literacy as much as drug design.

Dan Padgett

December 27, 2025 AT 04:35It’s like the universe gave us a hammer and told us to fix a clock. We hit the gears, the springs, the glass - sometimes we fix it, sometimes we break it worse. But hey, at least we’re trying. Maybe one day we’ll learn to use tweezers instead.

Hadi Santoso

December 27, 2025 AT 08:29so statins bind to 100+ proteins?? wait that means my muscle pain might not even be from the statin?? i thought i was just old… or maybe the statin just vibin’ with my muscles?? 😅

Kayleigh Campbell

December 28, 2025 AT 14:54So the reason your drug costs $5000 is because they had to test it against 200 proteins to make sure it didn’t turn your spleen into a disco ball? Cool. Glad we’re getting our money’s worth.

Dave Alponvyr

December 30, 2025 AT 09:42On-target = working as designed. Off-target = the drug got lost.

Mike Smith

January 1, 2026 AT 01:21Thank you for this nuanced and deeply informative exposition. The distinction between on-target and off-target effects is not only scientifically vital but ethically imperative for informed consent. Patients deserve to understand that side effects are not necessarily failures of the pharmaceutical process, but rather inherent manifestations of biological complexity. The shift toward phenotypic screening and AI-driven polypharmacology prediction represents a paradigm evolution - one that honors both the precision of molecular biology and the irreducible variability of human physiology. This is not merely pharmacology; it is the art of healing with humility.