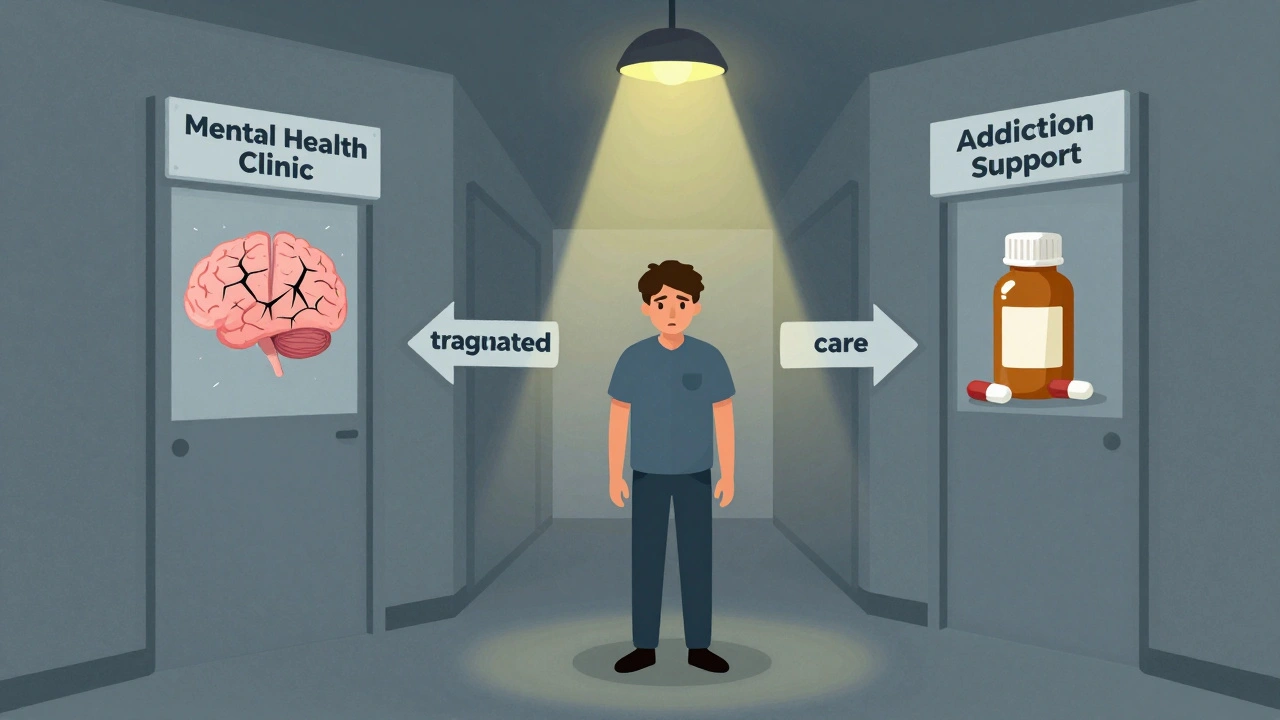

Imagine needing help for depression and alcohol use at the same time. You go to a mental health clinic, and they tell you to see a different office for addiction support. Then you go there, and they say you need to stabilize your mood first. You’re caught in the middle-torn between two systems that don’t talk to each other. This isn’t rare. It’s the norm for millions of people. That’s why integrated dual diagnosis care isn’t just better-it’s the only way forward.

Why Separate Treatments Fail

For decades, mental health and substance use were treated like two separate problems. One clinic for anxiety. Another for drinking. You’d get one set of meds, then another set of counseling sessions, often weeks apart. But here’s the problem: they don’t work in isolation. If you’re struggling with schizophrenia and using cocaine to quiet the voices, treating just the psychosis leaves you without tools to stop using. If you’re in recovery from opioids but your PTSD flares up, the cravings come back fast. The two feed each other. That’s why parallel treatment-where services run side by side but never connect-has been shown to be costly, inefficient, and ineffective. People fall through the cracks. They get confused. They give up. Studies show that only about 6% of people with co-occurring disorders get both mental health and substance use care at the same time. That means over 15 million adults in the U.S. are stuck in a broken system. The result? Higher hospitalizations, more arrests, longer relapses, and deeper isolation.What Integrated Dual Diagnosis Care Actually Looks Like

Integrated Dual Disorder Treatment (IDDT) is the gold standard for fixing this. It’s not a new drug or a fancy app. It’s a way of organizing care so that one team, in one place, handles both conditions at once. Think of it like this: instead of seeing two different doctors, you meet with one clinician who understands both mental illness and addiction. They don’t treat one first and then the other. They treat them together. Your treatment plan includes medication for bipolar disorder and strategies to reduce drinking-all in the same conversation. The model, developed in the 1990s at Dartmouth and refined by the Center for Evidence-Based Practices, includes nine core components:- Motivational interviewing to help you find your own reasons to change

- Substance abuse counseling focused on triggers and cravings

- Group therapy that mixes people with similar struggles

- Family education so loved ones understand both conditions

- Connection to peer support groups like Alcoholics Anonymous or SMART Recovery

- Medication management tailored for dual diagnosis

- Health promotion-nutrition, sleep, exercise

- Specialized support for those who aren’t responding to standard treatment

- Relapse prevention built around real-life scenarios

Harm Reduction: Not Abstinence, But Progress

One of the biggest shifts in IDDT is letting go of the idea that recovery means total abstinence from day one. That mindset pushes people away. If you’re using heroin to cope with severe depression, telling you to quit cold turkey doesn’t work. It just makes you feel like a failure. IDDT uses harm reduction. That means: if you’re still using, we’ll help you use less dangerously. We’ll connect you with clean needles. We’ll teach you how to recognize an overdose. We’ll help you avoid mixing substances with your meds. We’ll celebrate small wins-like cutting back from daily use to three times a week. This isn’t giving up. It’s meeting people where they are. And it works. People who feel judged leave treatment. People who feel understood stay.

Who Delivers This Care?

IDDT doesn’t work unless the team is trained in both worlds. That’s rare. Most therapists know mental health. Most addiction counselors know substance use. Few know both. The best programs train clinicians to be dual experts. They learn how SSRIs interact with alcohol. How psychosis can mimic withdrawal. How trauma histories shape addiction patterns. They use motivational interviewing-not to push change, but to explore it with you. But here’s the catch: training alone isn’t enough. A 2018 study found that even after three days of IDDT training, clinicians didn’t improve their skills in motivational interviewing. That means good intentions aren’t enough. You need ongoing supervision, coaching, and support. Teams need to be stable. Caseloads need to be small. Staff need to feel supported. Otherwise, burnout sets in-and the people who need this care the most get lost again.What the Data Really Shows

Some critics say IDDT doesn’t improve everything. Yes, the 2018 study found reduced substance use-but no big improvements in mood symptoms, social functioning, or motivation. That’s true. But it’s not the whole story. The Washington State Institute for Public Policy found that IDDT reduces alcohol use disorder symptoms by 16.5% and illicit drug use by 20.7%. That’s measurable. That’s real. The benefit-cost ratio is low-meaning it costs more than it saves right now. But that’s because we’re not funding it properly. We’re still paying for emergency rooms, jail stays, and homelessness because we won’t invest in prevention. And here’s what patients say: they feel heard. They don’t have to repeat their story twice. They don’t get told they’re “not ready” for one service because they’re “too unstable” for another. One person told researchers, “I finally felt like I wasn’t broken into pieces.”The Gap Between Need and Care

About 20.4 million U.S. adults have a dual diagnosis. Only 6% get integrated care. That’s not a coincidence. It’s a failure of policy. Funding is split. Mental health services get Medicaid dollars. Substance use programs get block grants. They don’t overlap. Insurance companies don’t cover both under one plan. Clinics can’t afford to hire staff trained in both areas. SAMHSA and other agencies have tried to fix this with grants and technical support, but without systemic funding changes, progress is slow. The solution isn’t more training workshops. It’s reimbursement reform. It’s integrated billing. It’s paying providers to treat the whole person, not just one symptom.

Where This Is Working

In places where IDDT is fully funded and staffed-like some assertive community treatment teams in New Hampshire, Minnesota, and Oregon-results are strong. Patients are more likely to stay housed. Less likely to be arrested. More likely to work or go to school. In the UK, similar models are being tested under NHS Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) and Community Mental Health Frameworks. While not always called IDDT, the principles are the same: one team, one plan, one person. The model isn’t perfect. But it’s the only one that doesn’t make you choose between being mentally ill and being addicted. It says: you’re a person. And you deserve care that sees all of you.What You Can Do

If you or someone you care about is struggling with both mental illness and substance use, ask for integrated care. Don’t accept being passed from one office to another. Ask: “Do you treat both conditions together?” If the answer is no, ask for a referral. If you’re a clinician, seek training in dual diagnosis. Learn how trauma, psychosis, and addiction interact. Advocate for team-based care in your organization. If you’re a policymaker, fund integrated programs. Change billing codes. Allow one payment for one person’s whole care. Stop treating mental health and addiction as separate problems. They’re not.It’s Not About Perfection. It’s About Presence.

You don’t need to be sober to start healing. You don’t need to be “stable” to get help. You just need someone who won’t look away. Integrated dual diagnosis care doesn’t promise a quick fix. But it promises something rarer: consistency. Compassion. And the quiet certainty that you’re not alone in your mess.What is integrated dual diagnosis care?

Integrated dual diagnosis care is a treatment approach that addresses both mental illness and substance use disorder at the same time, by the same team, in the same setting. It avoids splitting care between separate providers and instead creates one unified plan that considers how each condition affects the other.

How is IDDT different from traditional treatment?

Traditional treatment often separates mental health and substance use services-you might see one provider for depression and another for alcohol use. IDDT brings both under one roof, with one team trained in both areas. This prevents confusion, reduces gaps in care, and helps patients feel understood as a whole person, not a collection of symptoms.

Does IDDT require complete abstinence from drugs or alcohol?

No. IDDT uses a harm reduction approach. The goal isn’t always immediate sobriety-it’s reducing harm. That might mean cutting down use, avoiding dangerous combinations, or preventing overdose. Progress is measured in safety and stability, not just abstinence.

Who benefits most from integrated care?

People with severe mental illnesses like schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression who also struggle with substance use benefit the most. But anyone with co-occurring conditions-such as PTSD and opioid use, or anxiety and alcohol dependence-can see improved outcomes with integrated care.

Why is integrated care so hard to find?

Funding is split between mental health and substance use systems. Insurance often doesn’t cover both under one plan. Clinicians rarely receive training in both areas. Without coordinated funding and workforce development, integrated programs struggle to survive-even though they’re proven to work better.

Is IDDT effective?

Yes, for key outcomes. Studies show IDDT reduces days of substance use and increases treatment retention. While it doesn’t always improve mood symptoms or social functioning in the short term, patients report feeling less confused, more supported, and more connected to care. Long-term, it reduces hospitalizations and arrests.

How can I find an integrated dual diagnosis program?

Start by asking your current provider if they offer integrated care. If not, contact your local mental health authority or state substance use agency. SAMHSA’s treatment locator can help, and many community health centers now offer dual diagnosis services. Look for programs that mention “co-occurring disorders,” “integrated treatment,” or “dual diagnosis team.”

Carolyn Ford

December 5, 2025 AT 03:08Karl Barrett

December 5, 2025 AT 22:19Isabelle Bujold

December 6, 2025 AT 11:45Joe Lam

December 7, 2025 AT 12:12Jenny Rogers

December 7, 2025 AT 14:55Rachel Bonaparte

December 9, 2025 AT 04:18Scott van Haastrecht

December 9, 2025 AT 11:45Chase Brittingham

December 9, 2025 AT 21:51Bill Wolfe

December 10, 2025 AT 14:05Ollie Newland

December 11, 2025 AT 21:43Rebecca Braatz

December 13, 2025 AT 13:12Michael Feldstein

December 14, 2025 AT 17:58jagdish kumar

December 14, 2025 AT 23:08