When you pick up a prescription for metformin, lisinopril, or ibuprofen, there’s a 90% chance it’s a generic drug. That’s not luck - it’s the result of a tightly regulated, highly technical process called the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). The FDA doesn’t just approve any pill that looks like the brand-name version. There’s a strict, science-backed pathway that every generic drug must follow before it hits pharmacy shelves. And if you’ve ever wondered why generics cost so much less but work just as well, the answer lies in this process.

What Makes a Generic Drug Legally Equivalent?

A generic drug isn’t just a copy. It has to be pharmaceutically equivalent and bioequivalent to the brand-name drug, known as the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). That means it must contain the same active ingredient, in the same strength, same dosage form (tablet, capsule, injection, etc.), and same route of administration (oral, topical, IV). No exceptions.

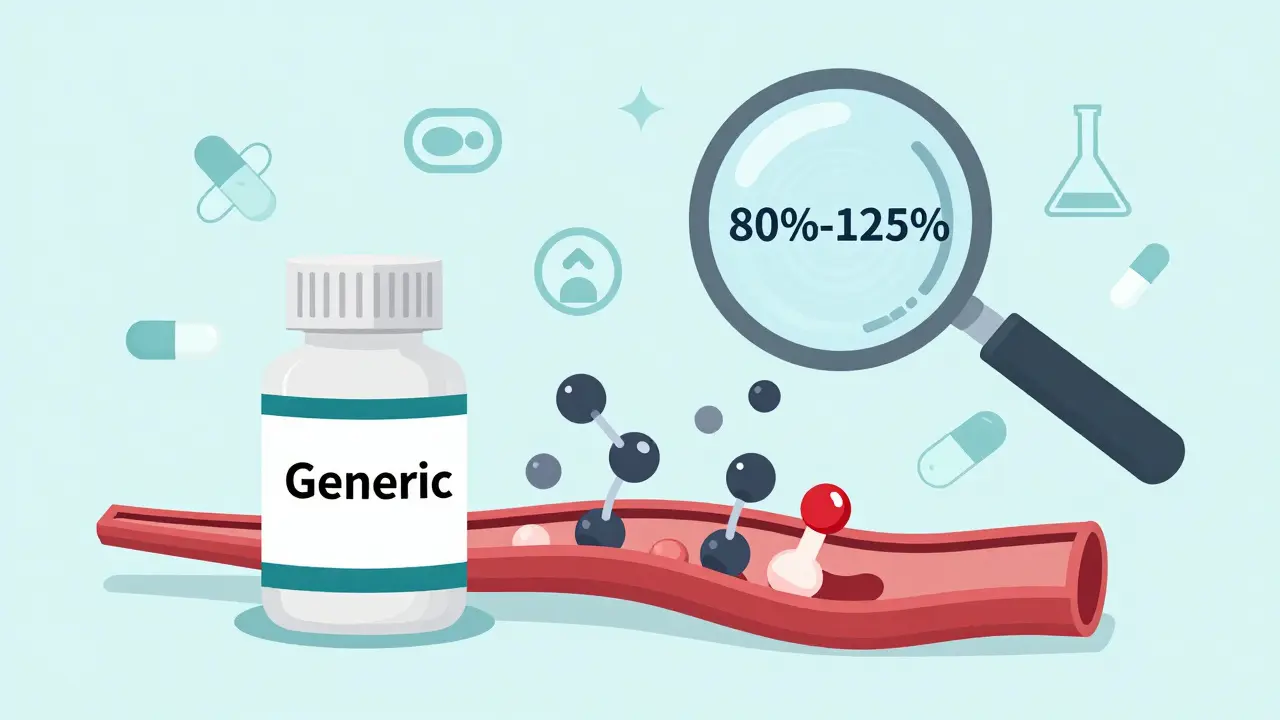

But here’s where most people get confused: it doesn’t have to look the same. The color, shape, flavor, or inactive ingredients (like fillers or dyes) can differ. What matters is how your body absorbs the medicine. That’s where bioequivalence comes in. The FDA requires that the generic delivers the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at the same rate as the brand-name drug. The acceptable range? Within 80% to 125% of the brand’s absorption levels - a narrow window that ensures consistent therapeutic effect.

This is why a generic version of warfarin, a blood thinner with a narrow therapeutic index, gets extra scrutiny. Even small differences in absorption can lead to dangerous outcomes. The FDA knows this. That’s why they review these cases more carefully - and why some generics fail even when they seem identical on paper.

The ANDA: The Backbone of Generic Approval

The entire process hinges on the ANDA. Unlike brand-name drugs, which require full clinical trials to prove safety and effectiveness (that’s the NDA pathway), generics don’t need to repeat those studies. The FDA already knows the RLD works. The ANDA’s job is to prove the generic matches it - down to the last detail.

Submitting an ANDA means providing four key data packages:

- Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC): This is the most common reason ANDAs get rejected. You need to show you can make the drug consistently, batch after batch. That includes details on raw materials, equipment, production methods, and quality control tests. The FDA checks whether your facility follows Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP). If your factory has had past violations, expect delays.

- Bioequivalence Studies: These are clinical trials - but small. Usually 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. They take the generic and the brand-name drug on different days, then blood samples are taken over hours to track how fast and how much of the drug enters the bloodstream. The study design must be approved by the FDA before it starts. If the protocol doesn’t meet their standards, you’ll get a Complete Response Letter (CRL) and have to restart.

- Labeling: The package insert must match the RLD exactly - same warnings, same dosing instructions, same contraindications. Minor changes to inactive ingredients can be noted, but the clinical information must be identical.

- Patent and Exclusivity Certifications: This is where legal battles begin. If the brand-name drug is still under patent, the generic applicant must certify one of four things: the patent is invalid, it won’t be infringed, the patent has expired, or they’re waiting for exclusivity to end. If they claim the patent is invalid or won’t be infringed (called a Paragraph IV certification), the brand-name company can sue - triggering a 30-month stay on approval. This is why some generics sit on the shelf for years, even after submission.

And everything must be submitted in the eCTD format - a standardized electronic structure with five modules. No PDFs. No Word docs. If your file isn’t organized correctly, the FDA won’t even accept it for review.

The FDA Review Timeline: What to Expect

Once the ANDA is submitted, the clock starts. Under GDUFA IV (2023-2027), the FDA aims to review 90% of original ANDAs within 10 months. But that’s not the whole story.

First, there’s a 60-day filing review. The FDA checks if your application is complete. If it’s missing key data - say, a bioequivalence protocol or cGMP documentation - you get a Refuse to Accept (RTA) letter. No review happens until you fix it. About 15% of ANDAs get RTA on first submission.

If it passes, the review begins. The FDA’s Office of Generic Drugs (OGD) assigns a team of scientists - chemists, pharmacologists, statisticians, reviewers. They look at every page. They might send you an Information Request (IR) asking for clarification. These aren’t rejections - they’re requests for more data. Most companies respond within 30 days. But if you take longer, the review clock pauses.

At the end of the review, you get one of two outcomes:

- Approval: Your drug is cleared for sale. The FDA updates the Orange Book, and you can start shipping.

- Complete Response Letter (CRL): The FDA says “not yet.” CRLs usually cite deficiencies in CMC, bioequivalence, or labeling. About 25% of ANDAs get a CRL. Some companies fix it and resubmit. Others abandon the application. One manufacturer told me their nasal spray ANDA got three CRLs over 28 months - costing over $2.3 million in extra testing.

On average, the first-cycle approval rate is 75%. That means most generics get approved on the first try - if they’re well-prepared.

Why Some Generics Take Longer Than Others

Not all generics are created equal. Simple tablets? Usually approved in 10-12 months. Complex products? That’s a different story.

The FDA calls these “complex generic drug products” - things like inhalers, injectables, ointments, gels, and transdermal patches. These aren’t just pills you swallow. Their effectiveness depends on how the drug is delivered - not just how much is in your blood. For example, an asthma inhaler must deliver the exact particle size to reach the lungs. If the propellant or nozzle design changes, the drug might not work the same way.

That’s why the FDA launched the Complex Generic Drug Products Initiative in 2023. They’ve issued draft guidance for 27 types of complex products. These require specialized testing, sometimes using animal models or advanced imaging. Reviewers need more time. Approval timelines can stretch to 24-36 months.

And then there’s the patent maze. If a brand-name drug has multiple patents - say, one for the formula, another for the pill coating, another for the method of use - the generic applicant has to navigate them all. The first company to successfully challenge a patent gets 180 days of market exclusivity. That’s why companies rush to file ANDAs on the day a patent expires. The first one in wins big - Humira’s first generic pulled in $1.2 billion in those 180 days.

Who’s Doing It and How Much Does It Cost?

Over 100 companies compete in the U.S. generic market. The big players are Teva, Viatris (which absorbed Mylan), and Sandoz. But hundreds of smaller firms are also filing ANDAs - especially for high-demand, low-cost drugs like antibiotics or diabetes meds.

The cost? A brand-name drug can cost $2.6 billion to develop. An ANDA? Between $1 million and $5 million. That’s why generics are so cheap. But don’t think it’s easy money. The upfront investment is still massive. You need scientists, regulatory experts, QA teams, and clinical trial coordinators. A single ANDA can involve 15-25 full-time employees working for over a year.

And the timeline? From start to finish, it takes 11-19 months just to prepare the application. Then add the FDA’s 10-month review. So if you’re planning to launch a generic, you’re looking at 2-3 years from concept to market.

Quality and Safety: Are Generics Really the Same?

Yes - and here’s the proof: 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics. That’s over 4 billion prescriptions a year. And the cost savings? $373 billion annually, according to the Association for Accessible Medicines.

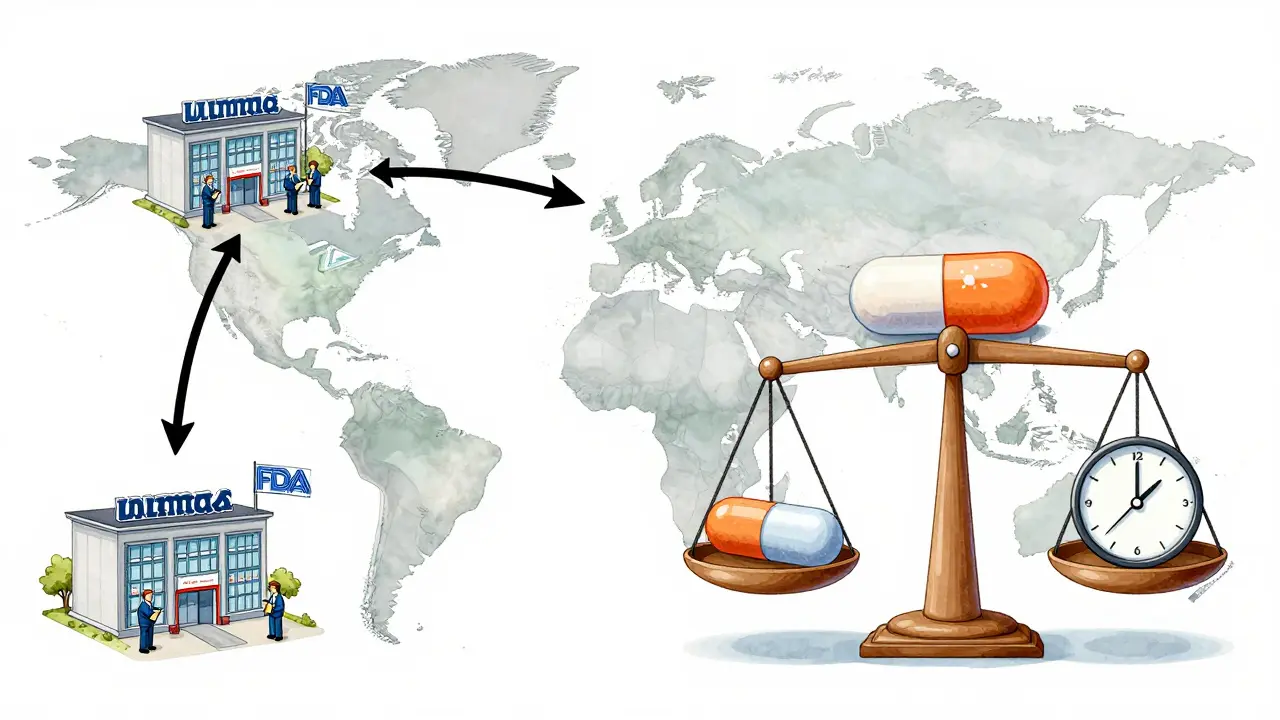

But skepticism remains. Some doctors worry about narrow therapeutic index drugs - like digoxin, lithium, or phenytoin. A 2019 JAMA study noted rare cases where switching generics caused clinical issues, often tied to manufacturing inconsistencies. The FDA doesn’t ignore this. They’ve increased inspections of foreign manufacturing sites - especially in India and China - where most active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) are made.

And here’s something most people don’t know: the FDA inspects generic drug facilities just as often as brand-name ones. In 2023, they conducted over 1,200 inspections of generic manufacturing sites. About 12% of those inspections found serious violations. Those companies are barred from selling until they fix the problems.

The bottom line? Most generics are safe. The FDA’s data shows they work just like the brand. But if you’re on a critical medication, talk to your pharmacist. They can tell you if your generic has been switched recently - and whether you should monitor for any changes.

What’s Next for Generic Drug Approval?

The FDA isn’t slowing down. Under GDUFA IV, they’re pushing to reduce the ANDA backlog from 1,200 applications in 2020 to under 300 by 2025. They’re also testing AI tools to automate parts of the review process - like sorting documents or flagging inconsistencies. Early results show a 25% reduction in administrative review time.

Biosimilars - generic versions of biologic drugs like Humira or Enbrel - are the next frontier. The FDA approved 5-7 biosimilars in 2023. By 2026, that number could hit 10-15. The approval pathway is similar to ANDAs, but even more complex because biologics are made from living cells, not chemicals.

For now, the ANDA system works. It’s not perfect. It’s slow, expensive, and full of legal hurdles. But it’s the reason you can fill a 30-day supply of atorvastatin for $4 instead of $300. It’s why millions of Americans can afford their meds. And it’s why the FDA will keep refining it - one application at a time.

How long does it take to get a generic drug approved by the FDA?

The FDA aims to review an ANDA within 10 months after it’s accepted for filing. But preparation takes 11-19 months before submission. So from start to approval, most generic drugs take 2-3 years. Complex products like inhalers or injectables can take 3-4 years due to additional testing and review.

Do generic drugs work as well as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generics to be pharmaceutically and bioequivalent to the brand-name drug. That means they deliver the same active ingredient at the same rate and amount into your bloodstream. Over 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are generics, and studies show they’re just as effective and safe for most people.

Why do some generic drugs get rejected by the FDA?

The most common reasons are problems with the Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC) section - like inconsistent production methods or poor quality control. Bioequivalence studies that don’t meet FDA protocols and labeling errors are also frequent causes. About 25% of ANDAs receive a Complete Response Letter (CRL) requiring fixes before approval.

Can I trust generics made overseas?

Yes. The FDA inspects all manufacturing facilities - whether in the U.S., India, China, or elsewhere - using the same standards as for brand-name drugs. In 2023, they conducted over 1,200 inspections of generic manufacturing sites. Facilities with serious violations are barred from selling until they fix the issues.

What’s the difference between an ANDA and an NDA?

An NDA (New Drug Application) is for brand-name drugs and requires full clinical trials to prove safety and effectiveness. It takes 6-7 years and costs over $2 billion. An ANDA (Abbreviated New Drug Application) is for generics and only needs to prove equivalence to an already-approved drug. It skips clinical trials, cuts costs to $1-5 million, and takes 3-4 years.

What is the Orange Book and why does it matter?

The Orange Book is the FDA’s official list of all approved drug products with their therapeutic equivalence ratings. If a generic is rated AB, it means it’s considered therapeutically equivalent to the brand-name drug and can be substituted without a doctor’s approval. Pharmacists rely on the Orange Book to know which generics can be swapped.

Why do some generic drugs cost more than others?

Price differences come from competition. The first generic to enter the market after patent expiry often gets 180 days of exclusivity and charges higher prices. Once other generics enter, prices drop 80-90%. Drugs with few manufacturers or complex formulations (like inhalers) also cost more because there’s less competition.

Can a generic drug be pulled from the market after approval?

Yes. If post-market data shows safety issues - like contamination, inconsistent potency, or unexpected side effects - the FDA can issue a recall or suspend approval. This has happened with several generics in recent years, especially those made at facilities with repeated cGMP violations.

Generic drugs are one of the most successful public health policies in modern medicine. They make treatment affordable, accessible, and sustainable. The ANDA process isn’t flashy - but it’s the quiet engine behind the $373 billion in annual savings. And for patients who need their meds every day, that’s everything.

Spencer Garcia

December 24, 2025 AT 00:28Just wanted to say this is one of the clearest breakdowns of ANDA I’ve ever read. The bioequivalence window (80-125%) is something most people don’t get, but it’s the whole reason generics are safe. No fluff, just facts.

Delilah Rose

December 25, 2025 AT 22:32I’ve been on generic warfarin for six years now, and I’ve had zero issues - but I remember when my pharmacist switched me from one generic to another and I felt weird for a week. Turns out, the fillers were different and my body needed to adjust. Not a failure of the system, just a reminder that even tiny changes matter when you’re on a narrow therapeutic index drug. The FDA’s extra scrutiny on these? Totally justified. I wish more doctors told patients this instead of just saying ‘it’s the same.’

Also, the part about CMC being the #1 reason for rejection? So true. I work in pharma QA, and I’ve seen companies spend millions on a single batch because they didn’t control humidity during tablet compression. It’s not glamorous, but it’s life-or-death stuff.

And don’t even get me started on the eCTD format. I’ve had to reformat entire submissions because someone sent a Word doc. The FDA doesn’t play. They’ll reject it before even looking at the science if the file structure is wrong. It’s like submitting a thesis with the wrong font.

People think generics are cheap because they’re low quality - but no, they’re cheap because the R&D cost is already paid. The real cost is in manufacturing precision. That’s why some generics cost more than others - it’s not greed, it’s complexity. A transdermal patch isn’t just a pill with a sticky side.

I’ve toured factories in India and China that make generics for U.S. pharmacies. The clean rooms are spotless, the staff are trained like surgeons. The FDA doesn’t cut corners, and neither should we assume they do.

The 180-day exclusivity thing? That’s capitalism at work. The first generic company to challenge a patent gets a monopoly for half a year - so they price high to recoup legal fees. Then ten others jump in, and suddenly it’s $4 for a 30-day supply. That’s the system working.

And yes, biosimilars are the next frontier. They’re not just ‘copies’ - they’re living molecules. One amino acid out of place and you’ve got a different drug. It’s not easy. But we’ll get there. The FDA’s AI tools? Already cutting review time. That’s progress.

Bottom line: if your doctor says ‘switch to generic,’ you can trust it. But if you feel off? Talk to your pharmacist. They’re the real gatekeepers.

Bret Freeman

December 27, 2025 AT 15:35Let’s be real - the FDA is just a corporate puppet. You think they care about patients? They care about patent extensions and Big Pharma’s bottom line. That 30-month stay on generics? That’s not science, that’s a legal loophole designed to keep prices high. And don’t even get me started on how many ‘generic’ manufacturers are owned by the same conglomerates that make the brand-name drugs. It’s all a rigged game.

And yet somehow, people still believe this ‘90% of prescriptions’ nonsense like it’s a miracle. It’s not a miracle - it’s a compromise. We’re just lucky the system hasn’t collapsed yet.

Also, ‘emoticon avoider’? Yeah, because I don’t need a 🤖 to tell me my medicine might kill me.

Lindsey Kidd

December 27, 2025 AT 21:35THIS. 🙌 I’ve been a pharmacist for 14 years and I see patients panic over generics all the time. They think ‘generic = cheap = bad.’ But honestly? The same pill, just without the logo. 💊

Pro tip: if you’re on a critical med, ask for the brand name’s manufacturer’s generic. Sometimes it’s made by the same company - just under a different label. And yes, the Orange Book is your best friend. Bookmark it. 📚

Austin LeBlanc

December 28, 2025 AT 18:06Wow. So you’re telling me the FDA actually does its job? I thought they were just a bunch of bureaucrats who approved pills because they were bribed by Indian factories. Turns out, they inspect 1,200 sites a year? That’s more than my ex checked my phone. Maybe I was wrong.

Also, who’s ‘Blow Job’? That’s not a name. That’s a Yelp review.

niharika hardikar

December 30, 2025 AT 01:46While the ANDA framework is ostensibly robust, the reliance on bioequivalence studies with small sample sizes (n=24–36) in healthy volunteers introduces significant translational limitations. The pharmacokinetic parameters derived from this cohort may not adequately reflect inter-individual variability in elderly, renally impaired, or polypharmacy populations. Consequently, therapeutic equivalence at the population level does not guarantee clinical equivalence in high-risk subgroups. The FDA’s current paradigm, while statistically sound, remains inadequately calibrated for real-world heterogeneity.

Rachel Cericola

December 31, 2025 AT 09:44Let me tell you something - if you’re still skeptical about generics, you’re not being cautious, you’re being misled by fear-mongering ads from brand-name companies. I’ve worked with the FDA’s OGD team on a few ANDAs. These reviewers are obsessed with detail. They’ll catch a 0.5% variance in dissolution profile that no one else would notice.

And yes, some generics fail. But that’s the point - the system filters them out. The ones you get at CVS? They passed. The ones that didn’t? They’re sitting in a warehouse in New Jersey, labeled ‘Rejected - Do Not Ship.’

Also, the ‘$1M–$5M’ cost? That’s for a simple tablet. A complex injectable? We’re talking $20M+. That’s why you don’t see generics for every drug - it’s not because they’re hiding them, it’s because the math doesn’t work.

And for the love of God, stop blaming India and China. The FDA inspects those facilities harder than they inspect U.S. ones. If your generic came from a facility with a history of violations, it would’ve been pulled already.

Trust the process. Not because it’s perfect - but because it’s the best we’ve got.

Blow Job

January 1, 2026 AT 04:59Man, this is the kind of post that makes me proud to be American. We don’t always get it right, but when we do - like this - it saves lives. I’ve got a kid on generic seizure meds. She’s thriving. No complaints. No drama. Just science working the way it should.

Thanks for taking the time to explain this so clearly. I’m sharing this with my whole family.

Ajay Sangani

January 2, 2026 AT 01:10Interesting how the system assumes bioequivalence equals therapeutic equivalence, yet human biology is not a controlled lab environment. Perhaps the real question is not whether generics work, but whether we are comfortable reducing human health to statistical tolerances. Is 80-125% acceptable for something that governs the rhythm of a heart or the firing of neurons? We have optimized for cost, but have we forgotten the soul of healing?

Pankaj Chaudhary IPS

January 2, 2026 AT 01:23As a public servant in India, I have witnessed firsthand how generic drug manufacturing has transformed healthcare access in rural communities. The ANDA framework, though American, has inspired similar regulatory reforms across Asia and Africa. The FDA’s rigorous standards are not just a U.S. asset - they are a global public good.

Let us not forget: the $373 billion saved annually doesn’t just mean lower bills. It means a diabetic in Bihar can afford insulin. A mother in Lagos can treat her child’s infection. This is not policy - this is justice.

Gray Dedoiko

January 3, 2026 AT 21:21Just wanted to add - I used to work in a pharmacy and we had this one guy who swore his generic blood pressure med made him dizzy. Switched him back to brand, he was fine. Switched him to a different generic - same as the first - no issues. Turned out he just hated the color of the pill. Weird, right?

People get attached to the look. It’s not the drug. It’s the packaging.

Sidra Khan

January 5, 2026 AT 04:4090% of prescriptions? Yeah, and 90% of people don’t know what’s in them. I’ll stick with my brand-name, thanks. At least I know who made it.