Imagine your child comes home from school with red, crusty sores around their nose. Or you wake up with a swollen, hot patch on your leg that’s spreading fast. These aren’t just rashes-they’re bacterial skin infections, and they’re more common than most people think. In the UK alone, impetigo and cellulitis make up a huge chunk of GP visits, especially in kids and older adults. The good news? They’re treatable. The bad news? Getting the diagnosis and treatment right matters more than ever because antibiotics aren’t working like they used to.

What’s the Difference Between Impetigo and Cellulitis?

Impetigo and cellulitis look similar at first glance-red, inflamed skin-but they’re totally different in how deep they go and how they spread.

Impetigo stays on the surface. It’s a shallow infection of the top layer of skin, the epidermis. You’ll usually see it on the face-especially around the nose and mouth. It starts as tiny blisters or pimples, then turns into oozing sores that form that unmistakable honey-colored crust. Kids between 2 and 5 are most at risk, and it spreads like wildfire in nurseries and schools. About 70% of cases are the non-bullous type. The other 30% are bullous impetigo, which affects babies under 2 and causes larger, fluid-filled blisters that burst easily.

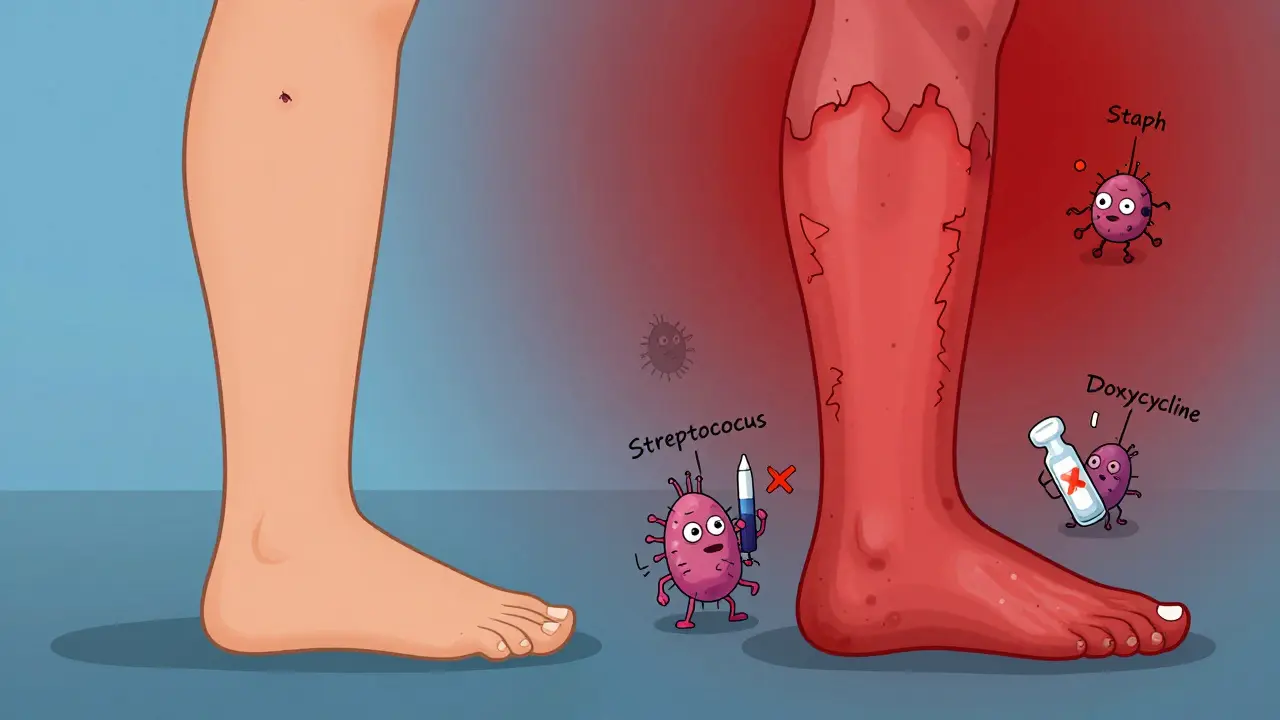

Cellulitis, on the other hand, digs deeper. It hits the dermis and the fatty tissue underneath. You won’t see a crust. Instead, you’ll notice a red, swollen, warm patch of skin that doesn’t have clear edges. It often shows up on the lower legs in adults, and it can spread quickly. Unlike impetigo, cellulitis isn’t contagious. It happens when bacteria sneak in through a cut, scrape, insect bite, or even a crack in the skin from athlete’s foot.

One key difference: impetigo is mostly caused by Staphylococcus aureus, sometimes mixed with Streptococcus pyogenes. Cellulitis? Usually Streptococcus pyogenes, with Staphylococcus aureus as a common second player. This matters because it changes what antibiotics work.

Why Penicillin Doesn’t Work Anymore

For decades, penicillin was the go-to for skin infections. But that’s history now. Around 85% of Staphylococcus aureus strains in the US and UK produce an enzyme called penicillinase that breaks down penicillin before it can kill the bacteria. That means if you’re still prescribing penicillin for impetigo, you’re probably wasting time-and letting the infection get worse.

Studies from the 1990s showed penicillin failed in about 68% of cases. Today, it’s even worse. In some areas, over half of community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus infections are now methicillin-resistant (MRSA). That’s not just a buzzword-it means drugs like flucloxacillin and cephalexin, which used to be reliable, might not work either.

That’s why doctors now start with antibiotics that actually kill these bugs. For impetigo, topical mupirocin (Bactroban) is the first-line treatment. It’s applied three times a day for five days. It works on 90% of cases if the infection is mild and limited. For more widespread or bullous impetigo, oral antibiotics like cephalexin or dicloxacillin are used. But if MRSA is suspected, doxycycline or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are better choices.

How Antibiotics Are Chosen Today

There’s no one-size-fits-all anymore. Treatment depends on three things: how bad the infection is, where it is, and what bugs are likely causing it.

For impetigo:

- Mild, localized: Topical mupirocin. Clean the area with warm soapy water first, gently remove crusts, then apply the ointment.

- Widespread or bullous: Oral antibiotics like cephalexin (25-50 mg/kg/day in two doses) for 7 days.

- MRSA suspected: Doxycycline (100 mg twice daily) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily) for 7-10 days.

For cellulitis:

- Mild: Oral cephalexin or dicloxacillin, 500 mg four times a day for 5-14 days.

- Severe (fever, swelling, spreading fast): Hospital admission, IV antibiotics like cefazolin (1-2 g every 8 hours).

- MRSA suspected: Add doxycycline or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole to the regimen.

There’s also a new option: topical retapamulin (Altabax). A 2024 study showed it cured 94% of impetigo cases in kids-making it a strong alternative if mupirocin isn’t available or if resistance is a concern.

When It Gets Dangerous

Most cases of impetigo clear up without trouble. But it can lead to something serious: post-streptococcal acute glomerulonephritis. That’s a kidney problem that can happen after a strep infection-even if the skin sore looks gone. It’s rare (1-5% of cases), but it’s why doctors still check urine in kids with strep-related impetigo.

Cellulitis? It’s far more dangerous. About 5-9% of cases lead to bacteria entering the bloodstream (bacteremia). In 0.3% of cases, it turns into necrotizing fasciitis-the flesh-eating infection you hear about in the news. And in 2-4% of hospitalized patients, it leads to sepsis.

There’s also Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome (SSSS). It’s rare, mostly in babies under 2, and it’s terrifying. The skin turns red, then peels off like a burn. It’s not an infection of the skin itself-it’s a toxin from Staphylococcus aureus that attacks the skin’s glue. If your child has a high fever and skin that looks like it’s been scalded, call emergency services immediately. Mortality is low with prompt treatment, but delay can be fatal.

What You Can Do to Prevent It

Prevention is easier than you think.

- Wash hands often, especially after touching sores or changing bandages.

- Keep cuts, scrapes, and insect bites clean. Use antiseptic cream and cover them.

- Don’t share towels, clothing, or bedding if someone in the house has impetigo.

- Treat athlete’s foot-it’s a common gateway for cellulitis.

- If your child has impetigo, keep them home from school or nursery until 24 hours after starting antibiotics, or until the sores are dry and crusted.

During outbreaks in schools or care homes, daily washing with antibacterial soap can cut transmission by up to 50%. That’s not just advice-it’s backed by data.

Why Diagnosis Matters More Than Ever

Doctors don’t always need a lab test. Impetigo is usually diagnosed by sight-the honey crust is unmistakable. Cellulitis? It’s also mostly clinical. But the tricky part is ruling out mimics: deep vein thrombosis, gout, or even allergic reactions can look like cellulitis.

That’s why antibiotics shouldn’t be handed out like candy. If you’ve had cellulitis before and it came back, or if it’s not improving after 48 hours, you need a culture. Same with impetigo that doesn’t respond to mupirocin. Resistance is rising, and we’re running out of options.

That’s why new tools are coming. The NIH is funding research into point-of-care tests that can identify the exact bacteria and its resistance profile in under 30 minutes. Imagine walking into a clinic, getting a quick swab, and walking out with a targeted antibiotic-not a guess.

What to Watch After Treatment

Even after the redness fades, keep an eye out.

- For impetigo: Watch for new sores or signs of kidney problems-swelling in the face or ankles, dark urine, or high blood pressure.

- For cellulitis: If the redness spreads again, you develop a fever, or the pain gets worse, go back. That’s not a relapse-it’s a warning.

Most people recover fully. But if you’re over 65, diabetic, or have poor circulation, you’re at higher risk for recurrence. That’s why ongoing skin care matters. Moisturize dry skin, manage diabetes tightly, and treat fungal infections fast.

Is impetigo contagious?

Yes, impetigo is highly contagious. It spreads through direct skin contact or by touching things like towels, toys, or bedding that have been contaminated. Children in nurseries and schools are most at risk. Once antibiotics are started, they’re no longer contagious after 24 hours.

Can cellulitis spread from person to person?

No, cellulitis is not contagious. It happens when bacteria from your own skin or a minor injury get into deeper layers. You can’t catch it from someone else, even if you touch their infected area.

Why do antibiotics sometimes not work?

Many strains of Staphylococcus aureus now produce enzymes that destroy common antibiotics like penicillin. Over half of community cases in the UK and US are now MRSA, meaning they’re resistant to drugs like flucloxacillin. That’s why doctors now use alternatives like doxycycline or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for suspected resistant cases.

How long does it take for impetigo to clear up?

With proper treatment, impetigo usually improves within 3 days and clears completely in 7-10 days. Without treatment, it can last weeks and may leave temporary skin discoloration. Crusting usually dries up in 48-72 hours.

When should I go to the hospital for a skin infection?

Go to the emergency room if you have a high fever, rapid spreading redness, severe pain, blisters or peeling skin, or if you feel dizzy, confused, or short of breath. These could be signs of sepsis, necrotizing fasciitis, or Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome-all medical emergencies.

Are there any new treatments for impetigo?

Yes. Topical retapamulin (Altabax) has shown 94% effectiveness in recent trials and is now an approved alternative to mupirocin, especially where resistance is a problem. It’s safe for children over 2 months and applied twice daily for 5 days.

What Comes Next?

The fight against bacterial skin infections is shifting. We’re moving away from broad-spectrum antibiotics and toward smarter, targeted care. That means better diagnostics, better stewardship, and better outcomes.

For now, the rules are simple: treat early, choose the right antibiotic, and don’t ignore the signs. If you’re unsure, see your GP. A small skin sore today could be a major problem tomorrow-if it’s not handled right.

Rob Deneke

January 17, 2026 AT 14:46Been there with my kid-impetigo spread like wildfire through daycare. Mupirocin saved us. Just clean the crusts gently, don’t pick, and keep towels separate. No drama, just results.

Bianca Leonhardt

January 18, 2026 AT 19:38People still use penicillin for skin infections? What planet are you on? This isn’t 1952. MRSA isn’t a rumor-it’s the new normal. Stop being lazy with prescriptions.

brooke wright

January 19, 2026 AT 14:02I had cellulitis last year after a mosquito bite got infected and I didn’t notice until my whole leg looked like a tomato. They gave me cephalexin and I thought I was fine after three days but then it came back worse. Turned out I had MRSA. Don’t stop antibiotics just because it looks better. Seriously. Your skin doesn’t lie.

Also, if you have diabetes? Moisturize. Like, every day. Dry skin is basically a welcome mat for bacteria. I learned the hard way.

And stop scratching your athlete’s foot. I know it’s itchy but that’s how it gets into your legs. I used to think it was just gross but now I get it-it’s a gateway. So gross but so true.

My cousin’s baby got SSSS. Like, one day she was fine, next day her skin was peeling off like a sunburn. ICU for a week. I didn’t even know that was a thing. Please tell your friends. Please.

And yes, retapamulin is a game changer. My dermatologist switched me to it after mupirocin failed. Same price, better results. Why isn’t this the first-line everywhere?

Also, hand sanitizer doesn’t kill spores. Soap and water. Always. I know it’s annoying but your hands are your first line of defense. No excuses.

My grandma’s doctor prescribed penicillin for her cellulitis last year. She ended up in the hospital. I cried. Don’t let this happen to your family.

And if you’re over 65? Check your feet. Every. Single. Day. I didn’t think it mattered until my uncle lost a toe. It’s not about aging. It’s about awareness.

And yes, kids with impetigo should stay home. No, it’s not overreacting. It’s science. Nurseries aren’t germ-free zones. They’re Petri dishes with snacks.

I wish I’d known all this before my daughter got sick. Now I’m the person who reminds everyone at the playground to wash hands. I don’t care if I’m annoying. I’d rather be annoying than bury someone.

And if you’re a parent? Keep a bottle of antibacterial soap by the sink. I keep one in my car too. You never know when your kid’s gonna scrape their knee on a rusty bike.

And yes, I’ve had three different skin infections since 2020. I’m not exaggerating. This isn’t rare. It’s epidemic. And we’re not talking about it enough.

So if you read this and think ‘eh, it’s just a rash’-you’re wrong. It’s not. It’s life or death sometimes. And we’re lucky we still have antibiotics at all.

Nick Cole

January 20, 2026 AT 17:38Just want to say thank you for this post. My mom had cellulitis last winter and the ER docs didn’t take it seriously until she started shivering. She’s fine now but I’ll never forget how close we came. This info could save someone’s leg-or life.

waneta rozwan

January 22, 2026 AT 11:51OMG I can’t believe people still think antibiotics are magic bullets. We’re literally breeding superbugs like we’re in a sci-fi horror movie. And nobody’s talking about it?!

My sister got MRSA from a tattoo. A TATTOO. And the artist didn’t even sterilize the needle properly. Now she’s on long-term antibiotics and can’t have kids because of kidney damage. This isn’t a joke. This is our future.

And why is no one pushing for better public health campaigns? We need billboards. We need school programs. We need a national panic. Not just a Reddit post.

Nicholas Gabriel

January 23, 2026 AT 04:15Thank you for sharing this detailed, clinically accurate, and urgently needed overview. I’ve been a nurse for 18 years, and I’ve watched the rise of MRSA firsthand-especially in long-term care facilities. I can’t stress enough: cleaning crusts with warm soapy water before applying mupirocin is non-negotiable. And yes, retapamulin is underused. It’s safe, effective, and doesn’t contribute to resistance the way oral antibiotics do. Also, for cellulitis, if the patient is febrile or immunocompromised, don’t wait-get them to the hospital. IV antibiotics aren’t a luxury-they’re a lifeline. And please, if you’re a parent, teach your kids not to pick at scabs. It’s not just ‘gross’-it’s a direct route to sepsis.

Cheryl Griffith

January 24, 2026 AT 02:13I used to think impetigo was just a ‘kids thing’ until my husband got it from shaving a razor nick. Took him three weeks to clear it because he ignored it. Now I keep mupirocin in our medicine cabinet like toothpaste. Simple. Effective. Don’t wait.

swarnima singh

January 26, 2026 AT 00:09so like... its not just about antibiotics right? its about how we treat our bodies? like we live in a world of fear and chemicals and we forget we are part of nature? like why do we think we can just kill everything? maybe we need to heal the soil and our skin too? like maybe the real problem is that we dont respect our bodies as sacred? like maybe we are the infection?

Jody Fahrenkrug

January 27, 2026 AT 22:40My daughter got impetigo last year. We did the mupirocin, kept her home, washed everything. No drama. Just basic hygiene. It’s not rocket science. Why do we make it so complicated?

Allen Davidson

January 28, 2026 AT 04:05People need to stop blaming antibiotics for resistance. It’s not the drugs-it’s the misuse. Taking them for viral infections, not finishing the course, hoarding prescriptions. The bacteria didn’t evolve because of science. They evolved because of laziness.

And yes, MRSA is scary. But so is ignoring early signs. If your leg is hot and red? Don’t wait for a fever. Go now. Your doctor isn’t judging you-they’re trying to save your limb.

john Mccoskey

January 29, 2026 AT 13:14Let’s be brutally honest: the medical system is failing us. We’ve turned skin infections into a commodity. Antibiotics are prescribed like candy because doctors are overworked, underpaid, and pressured to ‘move patients.’ The real issue isn’t resistance-it’s systemic neglect. We don’t invest in prevention because it doesn’t generate revenue. We don’t fund point-of-care diagnostics because Big Pharma profits more from broad-spectrum drugs. This isn’t a medical crisis-it’s a capitalist one. We’re treating symptoms while the system rotts from within. And you think a Reddit post will fix that? Please. The only thing that’ll change this is a complete overhaul of healthcare incentives. Until then, we’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic while bacteria multiply.

Joie Cregin

January 29, 2026 AT 23:34This is the kind of post that makes me feel less alone. My niece had SSSS and it was terrifying. I didn’t know what was happening until the ER doc said ‘it’s a toxin’ and I thought ‘what kind of nightmare is this?’ But knowing what to look for? That’s power. Thank you for writing this like a human, not a textbook.

Melodie Lesesne

January 30, 2026 AT 10:03My mom’s a nurse and she’s always saying ‘clean it, cover it, watch it.’ I never listened until I got cellulitis. Now I’m the one reminding everyone to wash their hands. Small things, big impact.

Corey Sawchuk

January 31, 2026 AT 03:16Had impetigo as a kid. My mom used honey on it. No joke. She swore by it. Turns out some studies now say raw honey has antibacterial properties. Maybe old-school stuff still works sometimes?

Christina Bilotti

January 31, 2026 AT 21:31Of course you’re recommending mupirocin. It’s expensive. Of course you’re not mentioning that 90% of rural clinics can’t afford it. You’re writing this from a place where antibiotics are a click away. Meanwhile, my cousin’s kid in Mississippi got a skin infection and waited three weeks for a telehealth appointment because Medicaid won’t cover the specialist. This isn’t about science. It’s about who gets care and who gets ignored.

Rob Deneke

February 1, 2026 AT 05:21Good point about access. My sister works in a rural clinic-she uses generic cephalexin and teaches parents how to clean sores with salt water if they can’t afford mupirocin. Sometimes the best treatment is education, not the latest drug.