GI-Related Bone Loss Risk Calculator

This tool estimates your risk of accelerated bone loss based on your gastrointestinal conditions and medication use. Based on medical research, chronic gut issues can increase osteoporosis risk by 30-70%.

Your Bone Loss Risk Assessment

Recommended Actions

Quick Summary

- Chronic gut problems can lower calcium and vitaminD absorption, speeding up bone loss.

- Inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, and long‑term use of acid‑suppressing meds each raise osteoporosis risk by 30‑70%.

- Screening bone density in anyone with a persistent GI condition catches problems early.

- Boosting gut health with diet, probiotics, and targeted supplements can slow bone loss.

- Treatment plans that address both gut inflammation and bone health give the best outcomes.

What Is Bone Loss?

When bone tissue breaks down faster than it rebuilds, the skeleton becomes porous and fragile - a process known as bone loss is the gradual reduction in bone mineral density that can lead to osteopenia or osteoporosis. In adults, a 1‑2% loss per year after age 30 is normal, but certain health issues can push that number much higher.

Understanding why bone loss happens is the first step to stopping it. The skeleton relies on a steady supply of calcium, vitaminD, and other nutrients, plus a balanced hormonal environment. Anything that disrupts absorption or increases inflammation can tip the scale toward net bone loss.

How the Gut Influences Bone Health

The gut and the skeleton talk to each other through several pathways:

- Nutrient absorption: Calcium and vitaminD are primarily taken up in the small intestine. Damage to the intestinal lining reduces the amount that reaches the bloodstream.

- Acid balance: Stomach acid helps dissolve calcium salts. Chronic use of proton‑pump inhibitors (PPIs) raises gastric pH, making calcium less soluble.

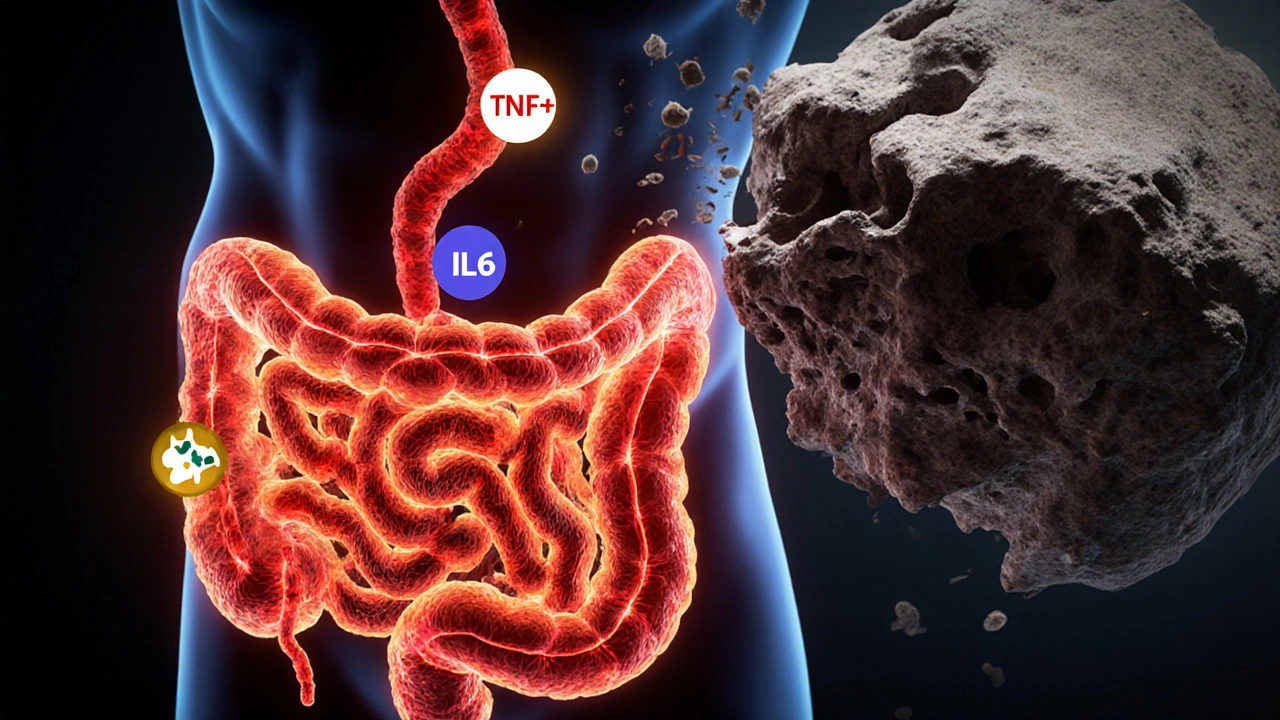

- Inflammatory cytokines: Chronic gut inflammation releases proteins like TNF‑α and IL‑6, which stimulate bone‑resorbing cells (osteoclasts).

- Gut microbiome: Certain bacteria produce short‑chain fatty acids that support calcium transport and may lower systemic inflammation.

- Hormonal signals: The gut releases hormones such as GLP‑2 that can promote bone formation; dysbiosis can blunt this effect.

Because these mechanisms overlap, a single gastrointestinal problem can impact bone health in multiple ways.

GI Disorders Most Linked to Accelerated Bone Loss

Not every stomach ache matters for the bones, but several chronic conditions have strong evidence of raising osteoporosis risk.

| Disorder | Key Mechanism | Relative Risk of Osteoporosis | Typical Bone‑Density Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) | Chronic inflammation, steroid use, calcium malabsorption | 1.5‑2.0× | 10‑15% lower BMD |

| Celiac Disease | Villous atrophy → poor calcium/vitaminD uptake | 1.4‑1.8× | 8‑12% lower BMD, especially lumbar spine |

| Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD) & Chronic PPI Use | Reduced gastric acidity impairs calcium carbonate absorption | 1.3‑1.6× | 5‑9% lower BMD at hip |

| Small‑Intestine Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) | Competition for nutrients, inflammation, altered bile acids | 1.2‑1.5× | Modest loss, often hidden until fracture |

| Helicobacter pylori Infection | Chronic gastritis reduces acid‑mediated calcium solubilisation | 1.2× | 4‑7% lower BMD in older adults |

These numbers come from meta‑analyses published in journals such as *Osteoporosis International* (2023) and *Journal of Gastroenterology* (2024). While the risk varies, the pattern is clear: long‑standing gut problems make bone loss more likely.

When to Get Your Bones Checked

Screening isn’t just for post‑menopausal women. If you fall into any of these groups, ask your doctor for a dual‑energy X‑ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan:

- Diagnosed with IBD, celiac disease, or chronic gastritis for more than a year.

- Regularly using PPIs, H2 blockers, or steroids for over six months.

- History of low‑trauma fractures (e.g., wrist, hip) before age 50.

- Family history of osteoporosis combined with a GI condition.

Early detection lets you intervene before a fracture occurs.

Nutrition & Lifestyle Strategies That Support Both Gut and Bone

Here’s a practical checklist you can start using today:

- Calcium source: Aim for 1,200mg daily from dairy, fortified plant milks, or leafy greens like kale. If you have malabsorption, calcium citrate is easier on the gut than calcium carbonate.

- VitaminD: 800‑1,000IU daily for most adults; higher (2,000‑4,000IU) if blood levels are below 20ng/mL. Sun exposure (10‑15minutes mid‑day) helps but may be limited for some patients.

- Protein: 1.0‑1.2g per kg body weight supports bone matrix formation. Include lean meat, fish, eggs, or plant‑based proteins like lentils.

- Probiotics & prebiotic fiber: Strains such as *Lactobacillus reuteri* and *Bifidobacterium longum* have been shown to improve calcium absorption in randomized trials (2022). Foods: yogurt, kefir, fermented veggies, and 25‑30g of soluble fiber from oats or fruit daily.

- Limit alcohol & smoking: Both increase gut permeability and stimulate bone resorption.

- Exercise: Weight‑bearing activities (walking, jogging, resistance training) 3‑4 times per week boost both bone density and gut motility.

For people on PPIs, swapping to calcium citrate or taking a calcium‑vitaminD supplement separate from the acid‑suppressing drug can mitigate the absorption issue.

Treatment Options When Bone Loss Has Already Started

If a DXA scan shows osteopenia or osteoporosis, your clinician may consider:

- Bisphosphonates: Inhibit osteoclast activity. Safe for most GI patients, but take with plenty of water and stay upright for 30minutes.

- Denosumab: A monoclonal antibody given subcutaneously every six months; useful for patients who can’t tolerate oral meds.

- Teriparatide: A synthetic parathyroid hormone that actually builds bone; reserved for severe cases.

- Addressing the underlying gut issue: Optimizing IBD therapy (biologics, immunomodulators), adhering to a strict gluten‑free diet for celiac disease, or eradicating *H. pylori* infection dramatically reduces ongoing bone loss.

Coordination between a gastroenterologist and an endocrinologist or bone specialist ensures that treatment tackles both sides of the equation.

Key Takeaways for Everyday Life

Summarising the medical details into everyday actions makes the information stick:

- Any chronic GI condition that messes with nutrient absorption or causes long‑term inflammation should flag you for a bone‑density test.

- Focus on calcium‑rich, vitaminD‑fortified foods and consider a supplement if your gut isn’t soaking up what you eat.

- Probiotic‑rich foods or a quality supplement can help restore a healthy gut microbiome, which in turn supports bone health.

- Stay active - weight‑bearing exercise benefits both gut motility and bone strength.

- When medication for your gut (like PPIs) is necessary, ask about the best calcium form and timing to keep bone loss in check.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can short‑term use of PPIs cause bone loss?

Short‑term (under 8weeks) PPI therapy usually doesn’t impact bone density. Problems show up after months of continuous use, especially when calcium intake is low.

Is a gluten‑free diet enough to protect my bones if I have celiac disease?

A strict gluten‑free diet heals the intestinal lining and improves calcium/vitaminD absorption, but many adults still need a calcium‑vitaminD supplement for the first year.

Do probiotics actually increase bone density?

Clinical trials have shown modest improvements (0.5‑1% increase in lumbar BMD) after 12months of specific probiotic strains, mostly when baseline calcium intake is adequate.

Should I get a DXA scan if I’m only on occasional ibuprofen for gut pain?

Occasional NSAID use alone isn’t a strong risk factor. Screening is recommended when the medication is combined with a chronic GI disease or long‑term steroid use.

Can losing weight help with bone loss caused by IBD?

Weight loss improves inflammation markers, but rapid or severe loss can also reduce mechanical loading on bone. Aim for a gradual, healthy reduction while maintaining adequate protein and calcium.

Jennifer Banash

October 13, 2025 AT 12:15It is a matter of grave concern that the intricate relationship between gastrointestinal pathology and skeletal integrity is often relegated to the peripheries of clinical discourse. The digestive tract, far from being a mere conduit for nutrients, orchestrates a symphony of hormonal and immunological signals that converge upon the bone matrix. When chronic inflammation ravages the intestinal mucosa, cytokines such as TNF‑α and IL‑6 spill over into systemic circulation, igniting osteoclastogenesis. Simultaneously, acid‑suppressive therapy dampens the solubilisation of calcium carbonate, yielding a silent deficit that accrues over months and years. Moreover, the villous atrophy characteristic of celiac disease obliterates the primary site of calcium and vitamin D absorption, engendering a cascade of hypocalcaemia and secondary hyperparathyroidism. The resultant bone turnover imbalance is manifested in a measurable reduction of bone mineral density, predisposing patients to fragility fractures. Epidemiological meta‑analyses have consistently demonstrated a 30‑70 % elevation in osteoporosis risk among individuals with long‑standing IBD or celiac disease. It follows that clinicians must adopt a proactive stance, integrating regular dual‑energy X‑ray absorptiometry (DXA) screening into the management algorithms for these patients. Nutritional rehabilitation, encompassing calcium citrate supplementation and judicious vitamin D repletion, constitutes the cornerstone of preventive therapy. Equally pivotal is the judicious use of proton‑pump inhibitors, reserving them for unequivocal indications and pairing them with calcium citrate when necessary. The gut microbiome, increasingly recognised as a modulator of bone homeostasis, may be nurtured through probiotic administration, thereby enhancing calcium transport and attenuating systemic inflammation. Lifestyle interventions-weight‑bearing exercise, smoking cessation, and moderation of alcohol intake-further bolster skeletal resilience. In sum, a multidisciplinary approach that addresses both gastrointestinal disease activity and bone health is indispensable for averting the inexorable march toward osteoporotic fracture. Let us, therefore, heed the evidence, embrace comprehensive screening, and implement targeted therapeutic regimens to safeguard the bones of those burdened by chronic gut disorders.

Stephen Gachie

October 21, 2025 AT 20:15The gut is not merely a pipe it is a philosopher of metabolism it asks the bones what they need and the bones answer in silence the chronic inflammation whispers louder than any shout the loss of acid is a quiet thief stealing calcium from the very marrow of our being it reminds us that every pill has a shadow the bone density scan is a mirror reflecting the hidden costs of our comforts it is a call to contemplate not just the gut but the whole tapestry of health

Sara Spitzer

October 30, 2025 AT 03:15Let me break this down point by point: First, the article correctly identifies the primary mechanisms-nutrient malabsorption, acid suppression, and inflammatory cytokines. Second, the risk percentages quoted (30‑70 %) align with the latest meta‑analyses from 2023‑2024. However, the piece could improve by specifying that the calcium‑citrate advantage is most pronounced in patients on PPIs, as calcium‑carbonate requires an acidic environment. Third, the recommendation to include probiotic strains like Lactobacillus reuteri is supported by a 2022 randomized trial showing a modest BMD increase. Lastly, while the table is helpful, it omits newer data on the gut‑bone axis mediated by GLP‑2, which is gaining traction. Overall, solid foundation but missing a few emerging nuances.

Jennifer Pavlik

November 7, 2025 AT 11:15Great summary! If you’re dealing with a GI condition, remember these simple steps: add calcium‑rich foods like yogurt and fortified plant milks, take a vitamin D supplement if you’re low, and try a daily probiotic for gut health. Even a short walk or light resistance training a few times a week can help keep your bones strong. Keep an eye on your doctor’s advice and ask about a bone‑density test if you’ve had a chronic gut issue for more than a year.

Jacob Miller

November 15, 2025 AT 19:15Honestly, most people think a occasional upset stomach isn’t a big deal, but the data shows otherwise. If you’re taking PPIs long‑term without monitoring calcium, you’re practically signing up for bone loss. It’s not an excuse to ignore the problem; it’s a sign you need a proper plan. Don’t just rely on vague “stay healthy” advice-get a DXA scan and talk to a specialist who actually knows the risks.

Anshul Gandhi

November 24, 2025 AT 03:15What nobody tells you is that the pharma industry pushes PPIs like candy while quietly eroding your bones. The “acid‑suppressing” narrative is a smokescreen for a profit‑driven agenda that doesn’t care about long‑term skeletal health. Independent studies have linked chronic PPI use to a 1.5‑fold increase in fracture risk-yet the labels stay silent. If you’re on these meds, demand calcium‑citrate and a bone‑density test. It’s the only way to protect yourself from a system that wants you dependent.

Emily Wang

December 2, 2025 AT 11:15Hey everyone, just wanted to give you a quick boost! If you have a gut issue, think of your bones as your personal cheer squad-keep them fed and they’ll keep you moving. Aim for at least 1,200 mg of calcium daily and don’t forget vitamin D. A short daily walk or a set of squats can make a huge difference. You’ve got this, stay strong and keep that gut happy!

Hayden Kuhtze

December 10, 2025 AT 19:15Oh wonderful, another reminder that your stomach is “broken” and now your bones are "sad" too. As if the world needed more drama. Sure, calcium citrate is “easier” on a compromised gut, but that’s just basic chemistry-no need for a headline.

Craig Hoffman

December 19, 2025 AT 03:15Check your calcium intake and get a DXA scan if you have a chronic gut issue.

Terry Duke

December 27, 2025 AT 11:15Great point, thanks for the reminder! , , , , , , , , , , , , , , ,

Chester Bennett

January 4, 2026 AT 19:15Everyone dealing with chronic GI conditions should remember that bone health isn’t a separate issue-it’s part of the same puzzle. A balanced diet, regular weight‑bearing exercise, and periodic DXA scans can keep the whole system in sync. Keep supporting each other and stay proactive!

Emma French

January 13, 2026 AT 03:15Your bones need the same attention you give your gut. Make sure to schedule a bone density test and discuss calcium‑citrate options with your doctor.

Debra Cine

January 21, 2026 AT 11:15Thanks for sharing all this info! 👍 It’s super helpful for anyone dealing with gut problems and worried about their bones. Remember, a bit of calcium, vitamin D, and some probiotic yogurt can go a long way. Stay healthy! 😊

Rajinder Singh

January 29, 2026 AT 08:09In the grand theatre of medicine, the silent partnership between gut and bone often takes a back‑stage role. Yet, when chronic inflammation steals the limelight, the bones suffer in tragic silence. Let us not ignore this drama; let us give it the audience it deserves with proper screening and holistic care.